Kushagra Kushwaha is a second-year master’s student at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

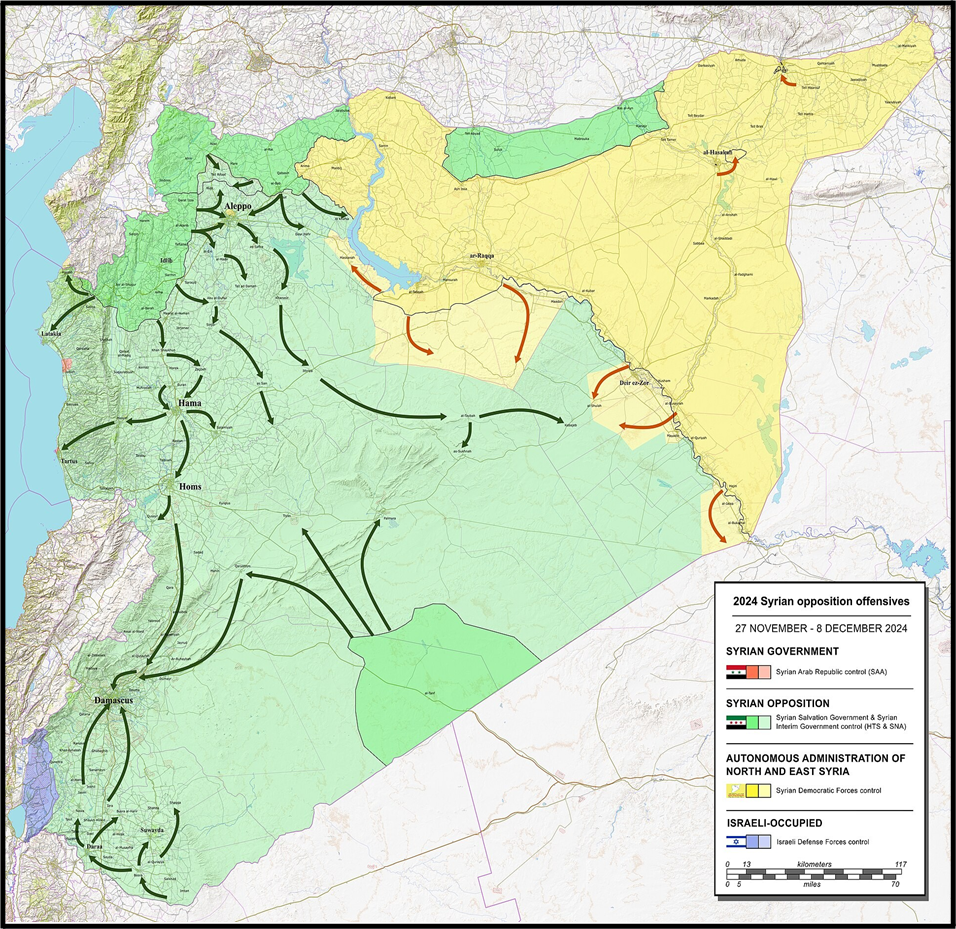

The collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 has forced Syria into a complex transition. This 14-year civil war has claimed over half a million lives, displaced nearly 14 million people, and left 16.7 million Syrians, over 70 percent of the population, in urgent need of humanitarian assistance, and obliterated an estimated US$ 800 billion in GDP. Today, the interim government led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) under Ahmed al-Sharaa has promised renewal but is facing daunting internal challenges and a web of external interests. The fall of Assad’s regime began when HTS, backed by the Turkish-supported Syrian National Army (SNA), launched Operation Deterrence of Aggression from Idlib (see Map 1). The attack was timed with a ceasefire between Lebanon and Israel, which left Hezbollah, Assad’s key ally, weak and unable to respond. Within weeks, Damascus fell, and Assad fled to Russia, ending over 50 years of Assad family rule. Multiple factors sped up this collapse. By December 2024, Syria’s economy had crashed, with the Syrian pound plunging from 1,150 to 17,500 per US dollar, while the military was plagued by corruption and disunity, relying heavily on illegal income like the US$ 2.4 billion Captagon drug trade. Meanwhile, external allies were unable to help; Russia was tied down in Ukraine, Iran was locked in a confrontation with Israel, and Hezbollah suffered significant losses from Israeli strikes. These internal failures and lack of outside support brought Assad’s regime to a rapid end.

Map 1. Operation Deterrence of Aggression

Source: Live Universal Awareness Map

The Transitional Government: Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham at the Helm

Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) began as a splinter from al-Qaeda’s Nusra Front during the early years of the Syrian civil war. After several rebrandings and mergers, it emerged in 2017 as a distinct and independent force. Though still designated a terrorist organization by the US and the EU, HTS dramatically changed its image after seizing Damascus in December 2024. Within weeks, its leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (formerly Abu Mohammed al-Julani) declared an interim government, primarily composed of figures from the Idlib-based Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), including key Islamist leaders. In March 2025, this transitional authority was formalized through a temporary constitution and a five-year roadmap leading to elections and national reform.

The new administration has promised unity and dialogue, and it launched a national consultation process to draft Syria’s future constitution. However, the dominance of HTS and its Islamist allies in the transitional government—despite support from other rebel groups, such as the National Front for Liberation — has raised eyebrows about the inclusivity of the political process. HTS didn’t rise to power overnight. Before its military victory, it had established a parallel state structure in Idlib, primarily funded through taxation, border revenues, and previously illicit sources of income, including smuggling and extortion. At its peak, control of crossings like Bab al-Hawa generated millions of dollars in annual revenue.

Militarily, HTS grew stronger through captured weapons, local innovation (including reports of 3D-printed arms), and indirect support from anti-Assad foreign backers like Turkey, the US, and Israel. However, while HTS’s battlefield success is undeniable, questions of legitimacy remain. Critics argue that military strength alone doesn’t build a stable state. As Hadi al-Bahra of the Syrian National Coalition put it, real legitimacy requires governance rooted in accountability, pluralism, and respect for human rights. With Syria still fractured and its future uncertain, HTS now faces its toughest test, not on the battlefield, but in the realm of governance. For some Syrians in Idlib, HTS’s Islamist focus has offered a semblance of order, with the rebuilding of infrastructure, such as minority religious sites, and essential services providing short-term relief in an otherwise chaotic landscape. Yet, for many others, including Alawites, Christians, Druze, and more secular Sunnis, HTS’s track record of human rights abuses and rigid religious interpretations sparks fear rather than hope. Organizations like Human Rights Watch and the Syrian Network for Human Rights have documented abuses that contradict HTS’s promises of inclusivity. Although the group has made gestures of tolerance, such as allowing Christian services, many remain skeptical without solid legal protections in place. In the end, HTS’s Islamist approach, coupled with its authoritarian streak, risks genuine unity and exacerbating the divisions that have already scarred Syria.

Internal Challenges

Syria’s reality post-Assad remains painfully bleak. Today, over 16.7 million Syrians, two-thirds of the entire population, are trapped in a devastating humanitarian crisis, urgently needing food, shelter, and basic healthcare, which points to HTS’s lack of administrative capacity. The transitional government is struggling with fragmented control as well, as a few months back (in January and February), clashes were occurring between the US-backed Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) in Northeastern Syria. As of March 2025, the Syrian interim government reached a landmark agreement with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) aiming to integrate the SDF’s civilian and military institutions into the Syrian state’s framework by the end of the year. The primary reasons for this agreement were to foster national unity, stabilize governance, and consolidate economic resources, particularly critical oil fields in northeastern Syria. Facilitated by America’s diplomatic efforts, this pact aimed to integrate the SDF’s experienced military forces into the national army, enhance security against remaining extremist threats and mitigate sectarian tensions by creating a more inclusive political framework, thus paving the way for post-conflict reconstruction and stability. Also, across the coastal regions, sectarian tensions have erupted into horrifying violence, especially in Alawite (Bashar al-Assad is an Alawite, and there are still loyal followers of him) strongholds like Latakia and Tartus (regions historically loyal to Assad), which have recently claimed over 1,500 lives in March 2025.

Three months after Assad’s fall, Syria remains stuck in instability. The transitional government struggles to assert control, with fragmented armed factions resisting central authority and former rebel groups still loyal to local commanders. Scholar Rahaf Aldoughli aptly describes current unification efforts as “fluff,” highlighting the lack of genuine integration. Economically, the outlook is equally bleak. Despite minor sanctions relief by the UK and EU, over 90 percent of Syrians remain below the poverty line, making Syria one of the world’s poorest nations. HTS’s Islamist rule also directly conflicts with the secular, Kurdish-led vision of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

While a US-brokered agreement in March 2025 brought the SDF into the national framework and recognized Kurdish representation, profound ideological differences remain. The SDF’s push for autonomy and cultural rights may be incompatible with HTS’s centralized religious model, raising concerns about the future of Kurdish freedoms under this arrangement. Still, limited cooperation between HTS and the SDF offers a narrow path toward stabilization. Power-sharing models, such as federalism, could bridge the divide, especially with continued international mediation.

Regional Dynamics: External Actors and Their Stakes

Syria’s ongoing transition is deeply influenced by a diverse and often conflicting array of external actors, each pursuing distinct interests and strategies:

European Union (EU) and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): The EU has pledged US$4.6 billion in direct grants, while urging protection for minorities. At the same time, GCC states like Saudi Arabia and Qatar have renewed ties with Syria through high-level visits, demonstrated its support for the new regime, and advocated for broader regional stability, including reforms in Lebanon.

Israel: It remains actively involved through military operations to secure its strategic interests, having conducted over 500 airstrikes in Syria since December 2024. In March 2025, Israeli strikes in Daraa showed their strategic intent to demilitarize southern Syria. Additionally, Israel has solidified its presence by indefinitely occupying a buffer zone in the Golan Heights, asserting this measure is essential to national security against any threats from Iranian-backed factions and other militants from within Syria.

Iran: Previously instrumental in supporting Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Iran has seen its influence significantly diminish due to Hezbollah’s retreat and Iran’s regional challenges. This reduction in Iranian presence has led to a power vacuum, raising concerns about the resurgence of Sunni militancy and other destabilizing forces filling the void left by Tehran’s reduced role. It also opened strategic opportunities for Syria’s transitional government. Accordingly, the new Syrian leadership is distancing itself from Iran, framing it as a source of sectarianism to attract support from Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This diplomatic pivot has already led to aid pledges and eased sanctions from Western countries. Syria is also pursuing economic liberalization to boost investment and promote regional integration while restoring ties with neighbors such as Turkey and Jordan to enhance trade and security. Despite ongoing unrest, this shift has offered a rare opportunity for Syria to reclaim sovereignty and reshape its regional standing.

Russia: While pulling back some troops due to the war in Ukraine, Russia still wants to keep its influence in Syria through its main bases at Tartus and Khmeimim. Still, in 2025, Russia stated that talks would continue to ensure the operation of these bases. Even with fewer soldiers and equipment, Russia plans to stay involved. At the same time, Syria’s new leaders have shown respect for Russia’s role but support a slow and respectful reduction of Russian forces to avoid any problems.

Turkey: Turkey’s primary aim is to create a safe zone along its border to prevent a Kurdish autonomous region that could embolden separatist movements within Turkey. Accordingly, its current vision for Syria centers on neutralizing threats from Kurdish groups like the YPG and SDF, which it links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a designated terrorist organization. It has supported the SNA through military operations like Operation Euphrates Shield and is engaging with the new transitional government led by HTS to ensure its security interests, including managing refugee flows and preventing the resurgence of ISIS. Its actions include backing the SNA and negotiating with HTS, reflecting its ambition to shape Syria in line with its neo-Ottoman goals.

US: The US is cautious in engaging with HTS, emphasizing minority rights and an inclusive transition while advocating for sanction relief if the new government proves stable. Currently, its vision for Syria focuses on combating ISIS, countering Iranian influence, and maintaining a military presence in the northeast to support the SDF in securing oil fields. America’s stance also creates tensions with Turkey over SDF support, highlighting the complexity of balancing counterterrorism with regional alliances.

After Assad’s fall, the EU lifted restrictions on key sectors like energy and banking to support Syria’s recovery. Qatar also agreed to supply natural gas to boost electricity. Meanwhile, the US kept most sanctions but allowed limited transactions, including energy deals. These moves show growing international support—driven not just by goodwill, but also by the desire to influence Syria’s future and access its resources.

The Path to Stability: Opportunities and Obstacles

The international community has shown notable support for Syria’s recovery after Assad’s fall. At the February 2025 Paris Conference, attended by the Syrian transitional government, nineteen coalition states, and major global organizations, there was a clear push for a unified and inclusive Syria through constitutional reform and future elections. Syria’s new leadership has also reached out to key players, including Turkey, Qatar, and the European Union, signalling a desire for regional legitimacy and broader cooperation. A significant milestone was reached on March 13, 2025, when Syria’s interim government signed a transitional constitution that blended Islamic principles with protections for minority rights and national sovereignty. Alongside this, efforts are underway to integrate scattered armed groups into a national army, though progress has been slow due to divided loyalties. A landmark agreement with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) promises citizenship and constitutional recognition for Kurds, and HTS is working to unify disparate militias under a centralized command, gradually shifting security duties to organized police forces. Yet, serious challenges remain. Sectarian tensions have resurfaced violently. In March 2025, clashes in Alawite-majority areas like Latakia and Tartus resulted in over 1,500 deaths, with reports from the UN confirming mass killings of civilians, including women and children. Retaliatory attacks and deep-rooted mistrust between factions threaten the fragile unity the transitional government is trying to build. The national military still lacks cohesion, and rogue battalions may act independently, further inflaming tensions. Sanctions, too, continue to hinder recovery. While some Western countries have eased restrictions, others, such as the UK and Canada, remain firm. According to the Atlantic Council, withholding broader sanctions relief could deliver a “fatal blow” to Syria’s recovery, especially given the US$800 billion in estimated war-related economic losses and the staggering poverty rate. External pressures from regional actors like Israel and Turkey complicate the situation further, while disinformation campaigns have eroded public trust in the new leadership.

Conclusion

Today, Syria stands at a critical crossroads. With Assad gone, the country has a chance to break from its painful past and build something hopeful. A new leadership, growing international support, and steps toward reform have opened the door to change. But challenges remain. Deep divisions, scattered armed groups, and ongoing violence still threaten the country’s fragile recovery. For Syria to move forward, promises must turn into real action. The new constitution, military unification, and agreements with groups like the SDF must lead to actual trust, inclusion, and stability on the ground. If the government can protect all communities, rebuild trust between different groups and continue working with international partners, Syria may finally begin to heal after years of conflict. Syria’s future will be decided not just by what was lost but by how wisely the country chooses to rebuild.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal.