Akhilraj P. Gangadharan is a second-year master’s student at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

Semiconductor chips are an indispensable part of every electronic equipment from smartphones to advanced defence systems, making them a strategic asset for technological leadership. The competition extends to future technologies like AI, 5G, and quantum computing, where dominance in semiconductor technology could dictate global standards and market influence. One must always investigate the complexity of supply/value chains, to clearly understand how a localised crisis or even global events like the pandemic, can hamper the supply of semiconductors worldwide. As the pandemic revealed the vulnerability of the semiconductor supply chains, disruption and the subsequent restructuring is happening as part of a grand rivalry unfolding between the US and China. Semiconductors lie at the heart of the US-China technological rivalry due to their critical role in modern technology, substantial economic impact, and national security implications. The rivalry between the two countries has led countries worldwide to look into their dependencies and vulnerabilities in this domain, which has pushed countries to adopt different strategies to increase resilience in the supply chain.

With nations worldwide competing for dominance in this economically intertwined sector, India’s strategic approach establish itself as a reliable player in the global semiconductor supply chain depends on its ability to capitalise on the current trend of offshoring supply chains away from China. Balancing considerations of economic development, national security, and future technological capabilities, India confronts a complex set of challenges and opportunities in formulating its semiconductor strategy.

Interdependencies and Vulnerabilities in the Semiconductor Supply Chains

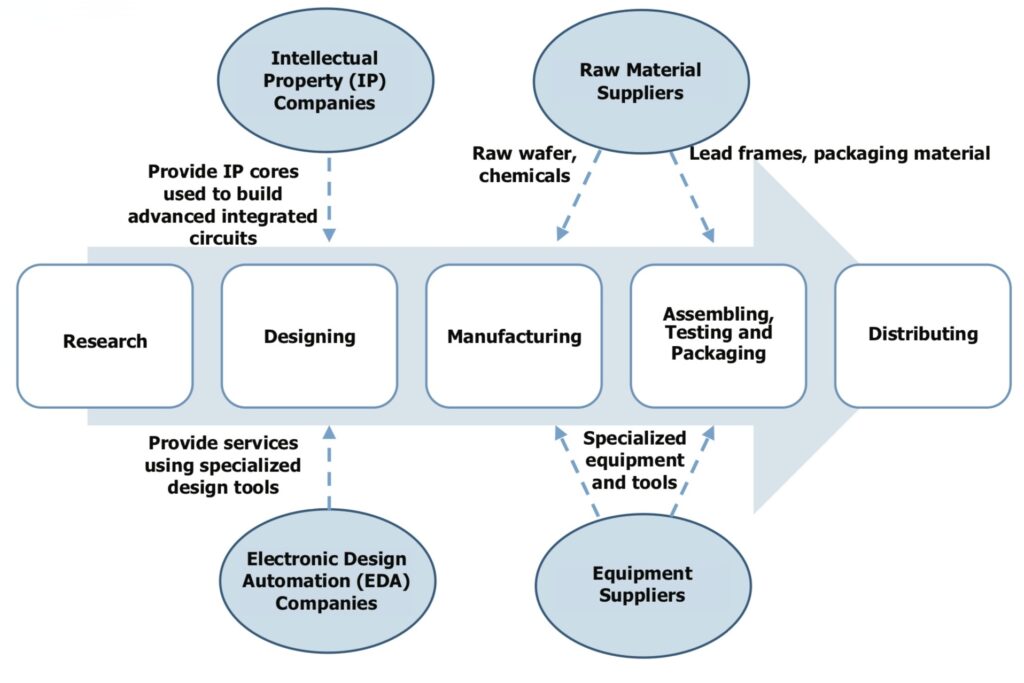

The Semiconductor industry is one of the most deeply globalised industries in the world. It comprises R&D, design, manufacturing, assembly, testing, packaging, and distribution. The industry thrives on continuous and rigorous innovation which requires great specialisation, adding significant value to the existing supply chains. The Semiconductor production begins with R&D and finally ends with distribution. The research and development acquire a critical importance in the value chain, as researchers constantly seek to increase the pace and processing power of semiconductor devices (following Moore’s Law), while minimising costs. The design stage involves conceptualising new products and specifications to meet customer demands and laying the groundwork for chip development. It heavily depends on research outcomes and requires a highly skilled workforce with strong engineering expertise.

The manufacturing stage focuses on producing the designed chips and demands advanced technical, chemical, and material expertise with exceptional precision. It is marked by high fixed costs and the continuous need for facility upgrades to keep pace with technological advancements. Achieving high-capacity utilisation (around 90 per cent) and large-scale operations is essential for success. The final stage of the semiconductor value chain is assembling, packaging, and testing the semiconductor device, which ensures proper connectivity for functionality. Compared to manufacturing, it incurs higher material and labour costs.

Figure 1: The Semiconductor Ecosystem

Source: Semiconductor Industry Association

The countries that occupy a major spot in the semiconductor ecosystem include the United States, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China and some European countries. The Cold War and the emergence of the neoliberal world order provided East Asia with a prominent role in the global semiconductor industry through various stages of the supply chain. During this era, the industry was not just an example of product innovation (which is essential according to Moore’s Law) but showcased substantial process innovation redefining the future of semiconductor production. For instance, the emergence of the fabless-foundries business has reduced the time-to-market of a chip and produced economies of scale, thus reducing labour costs.

The shift of semiconductor manufacturing to East Asia in the recent decades, has contributed to the interconnection between two geographically distinct network of companies. One of the factors that has contributed to this phenomenon is the emergence of China as a major assembly location for electronics/ICT products, which made it the largest market for semiconductors since 2005. Second, the evolution of IDM (Integrated Design Manufacturers) model of semiconductor manufacturing to fabless/foundry model had led to high optimisation in the semiconductor global value chain. The rise of China coupled with its advancement in semiconductor manufacturing (driven by state subsidies) presents the United States with a unique set of problems. Extensive subsidisation of Chinese semiconductor firms through State Owned Enterprises raises added concern about their impact on trade flows, potentially disadvantaging emerging economies by reducing trade, investment, and technology transfers.

Understanding the global significance of semiconductor manufacturing is crucial, especially as major economies introduce substantial incentive programs to attract manufacturers. The inherent reason behind such subsidisation is important to note. Historically, chip manufacturing has been a critical technology with a high risk of failure; therefore, the profit margins in this industry are relatively low. Around the world, these technologies are incubated with public funds, while control over them remains under the purview of governments. The United States, for instance, has launched a chip incentive plan with a budget of approximately US$50 billion. Similarly, the European Union is striving to enter the semiconductor supply chain and has introduced an incentive program comparable to that of the U.S.

The technological rivalry was a major test in understanding the resilience of the supply chain. Donald Trump’s 2016 victory in U.S. presidential elections marked a turning point in US-China relations. His administration sought to manage trade through tariffs and urged American companies to leave China. In 2017, the U.S. sanctioned Chinese telecom giant ZTE for perjury, barring American firms from doing business with it, escalating the trade war into a technological rivalry. By 2018, the US tightened export controls on key technologies to curb Chinese acquisitions. In 2019, the U.S. accused firms like Huawei of stealing trade secrets, intensifying the trade war. Rising labour costs and political concerns pushed U.S. firms to reconsider dependence on China. Trump’s export controls targeted China’s semiconductor industry, which lacked essential manufacturing tools. This hurt Huawei as U.S. firms like Synopsys cut supplies, and European firms like ASML faced pressure to halt sales. The Biden administration continued these policies, formalising chip access restrictions to hinder China’s military modernisation. In October 2022, the Bureau of Industry and Security tightened export controls, reinforcing U.S. technological superiority. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 responded to these challenges.

Beyond geopolitics, supply chain disruptions have shown how vulnerable the semiconductor industry can be. The COVID-19 pandemic led to factory shutdowns and transportation bottlenecks, causing severe chip shortages that impacted industries such as automotive manufacturing. Natural disasters, such as earthquakes in Taiwan or power outages in South Korea, can also disrupt chip production. Given these vulnerabilities, many companies and governments are now seeking diversification strategies, investing in domestic semiconductor production, and building alternative supply chains to reduce dependence on any single country. This presents a significant opportunity for emerging economies like India and Vietnam to strategically establish their position in the global semiconductor ecosystem.

India’s Semiconductor Strategy

India’s push towards a semiconductor strategy gained momentum in the post-pandemic period due to supply chain disruptions caused by COVID-19 and US-China trade tensions. This reinvigorated the Indian government’s efforts to develop its semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem after several failed attempts in the past. India’s 2007 semiconductor policy failed due to insufficient financial incentives (20-25 per cent support), a skewed cost-benefit ratio with only US$28 billion in domestic electronic exports, and delays in implementation. These issues have caused India to rethink its strategy to attract semiconductor investments and integrate into global supply chains.

By simultaneously building all the essential stages of the semiconductor supply chain India’s new semiconductor strategy aims to initially meet the domestic demands and then subsequently cater to the burgeoning global market. Given its strong presence in chip design, the Indian government is now focusing on establishing semiconductor fabs to meet the needs of downstream industries such as automotive, electronics, smartphones, and home appliances. This is expected to create jobs across multiple sectors. To attract foreign investment, India has launched a US$10 billion Modified Programme for Semiconductors and Display Fab Ecosystem, offering up to 50 per cent financial support for projects in various semiconductor domains, including Silicon Fabs, Display Fabs, and Semiconductor Packaging. Currently, three major semiconductor fabrication plants are under construction with a combined investment of approximately Rs. 1.25 trillion. The first, in Dholera, Gujarat is being developed by Tata Electronics in partnership with Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (PSMC) and aims to produce its first chip by late 2026. The second, an OSAT facility in Morigaon, Assam, also by Tata Electronics, will cater to electric vehicles, automotive, mobile phones, and power devices. The third, located in Sanand, Gujarat, is an OSAT facility being developed by CG Power and Industrial Solutions Limited under the ATMP scheme. Additionally, a new semiconductor plant in Sanand, Gujarat, with an investment of Rs. 3,300 crores, is being established by Kaynes Semicon Pvt. Ltd. This facility will produce 6 million chips daily. The government plans to increase the financial support for the second phase of its chip manufacturing incentive scheme to US$15 billion, aiming to further boost investment and accelerate semiconductor production nationwide.

The Indian government is addressing the talent gap in the semiconductor industry by simultaneously developing a skilled workforce alongside the sector’s growth. A primary focus will be on R&D to meet the rising demand for specialized professionals tailored to the semiconductor industry. Union IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnav announced that the government has acquired Electronic Design Automation (EDA) tools from companies like Cadence, Synopsys, and Siemens and distributed them to 104 universities across India, including not only the IITs but also tier-II and tier-III institutions. This initiative gives students access to real-time tools, fostering the growth of start-ups that will expand the talent pool. This talent pool will further support India’s broader base of engineers, enabling them to contribute to the Design, Fabrication, and ATMP sectors of the semiconductor ecosystem. The minister emphasised that this will be a comprehensive initiative, not only aimed at building the semiconductor industry but also equipping skilled workers to meet future domestic and global demands. India also being a QUAD member has been receiving special attention from the United States in developing the semiconductor technology by bolstering supply chain security for allies and partners, emphasising the role of multilateralism in enhancing strategic cooperation.

The current geopolitical confrontation over technology has made India realise the strategic imperative of developing a resilient and self-sufficient semiconductor industry. It is expected that India will become the largest consumer of semiconductors by 2030, estimated to be around US$110 billion. Despite significant challenges concerning high capital costs, skilled workforce, and technology transfer restrictions, India is making significant strides in developing the semiconductor ecosystem through strategic partnerships, government initiatives and educational investments. Therefore, the future looks promising as India’s semiconductor strategy paves the way for a strong presence in the global semiconductor ecosystem.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal.