Pavan Chudasama is a second-year master’s student at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

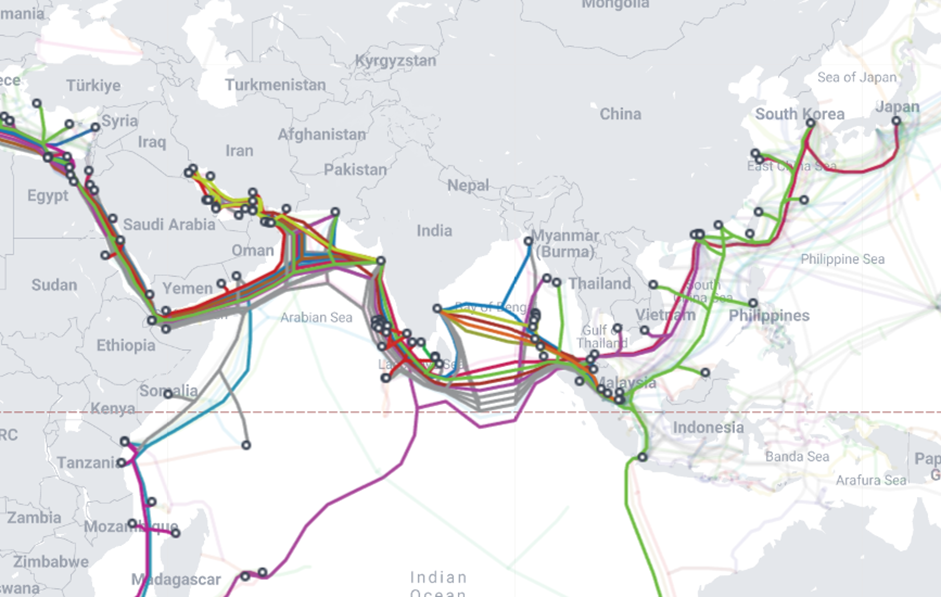

Undersea cables form the backbone of global telecommunications, carrying approximately 95 percent of the world’s communications through a network of 597 cable systems and 1,712 landing stations, spanning 1.48 million kilometers as of 2025. These cables support critical functions, including economic transactions, military communications, and daily connectivity. TeleGeography estimates that over USD 5 trillion in financial transactions traverse these cables daily, highlighting their strategic value. The United Nations General Assembly has acknowledged undersea cables as “critical communications infrastructure” essential to global economies and national security. Despite their importance, these cables remain vulnerable to a range of threats, often overlooked in policy discussions.

Source: TeleGeography

Major Threats to Undersea Cables

Undersea cables face multiple vulnerabilities, categorised into natural threats, human-induced incidents, and deliberate sabotage, each posing distinct challenges to their integrity. Natural threats such as seismic events, tsunamis, earthquakes, and extreme weather significantly jeopardise cable functionality. While the natural threats account for less than 20 per cent of cable faults, their impact can be widespread. When these events occur, they often damage multiple cable systems across vast areas, causing severe disruptions, especially in regions that rely on fewer cables for connectivity.

Some of the natural incidents include the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that caused prolonged outages in Southeast Asia, as the intense pressure on shallow-water cables led to significant disruptions in regional connectivity. In 2009, tropical cyclones severed subsea cable links to Taiwan, disrupting communications across Asia. In 2011, a massive undersea earthquake off the coast of Japan generated a powerful tsunami, inflicting severe damage on undersea cables, impairing nearly half of the trans-Pacific network, affecting global communication links. The 2022 Tonga volcanic eruption severed the nation’s sole cable, isolating it from global networks critical for disaster response.

Human-induced threats, primarily from fishing and anchoring, constitute most of the cable damage. The International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC) attributes that to around 150–200 cable faults occurring worldwide each year. Of these, approximately 70–80 per cent result from accidental damage, primarily caused by fishing and ship anchors, which frequently disrupt undersea communication networks. In 2008, multiple Mediterranean cable breaks disrupted internet services in Central Asia and India, while 2012 saw East Asian connectivity failure due to similar activities. The West Africa Cable System (WACS) experienced repeated anchor-related faults in 2017, affecting African nations’ connectivity. These incidents underscore the need for better awareness and regulation of maritime activities near cable routes.

Deliberate sabotage of undersea cables is a growing concern, especially as global tensions rise. For India, this poses a major risk to both national security and economic stability. As the country continues to expand its digital infrastructure, undersea cables play a crucial role in keeping communication and internet services running smoothly. Since many of these cables pass through the Indian Ocean—a region often contested by various powers—they are exposed to potential attacks looking to disrupt vital connections and gain an advantage. Protecting these cables is essential for maintaining stability and ensuring uninterrupted access to information and services. A historical precedent was set by Britain cutting five German cables during World War I, which crippled Germany’s global communications. Today, advancements in maritime technology have introduced sophisticated tools that amplify these risks. In 2025, China revealed the first officially disclosed technology of its kind—a compact deep-sea cable-cutting device capable of severing highly reinforced underwater communication and power lines at depths of up to 4,000 meters, beyond the reach of most existing cable infrastructure. While designed for civilian applications like seabed mining, its dual-use potential raises alarms, particularly for India. The Indian Ocean, a critical artery for global trade and connectivity, is a focal point of India-China strategic competition. A tool like this could target cables vital to India’s digital connectivity, threatening its economic stability and military communications, especially during periods of heightened tensions. Recent incidents further highlight these vulnerabilities. In March 2024, three Red Sea cables were damaged, disrupting 25 percent of Asia-Europe data traffic, including systems critical to India’s connectivity. Suspicions of sabotage linked to Houthi rebel activities in the region underscore the risks in contested maritime zones. For India, similar threats loom in the Indian Ocean, where regional instability and geopolitical rivalries could expose cables to intentional harm. To mitigate these risks, India must prioritize robust protection measures to secure its digital and strategic interests.

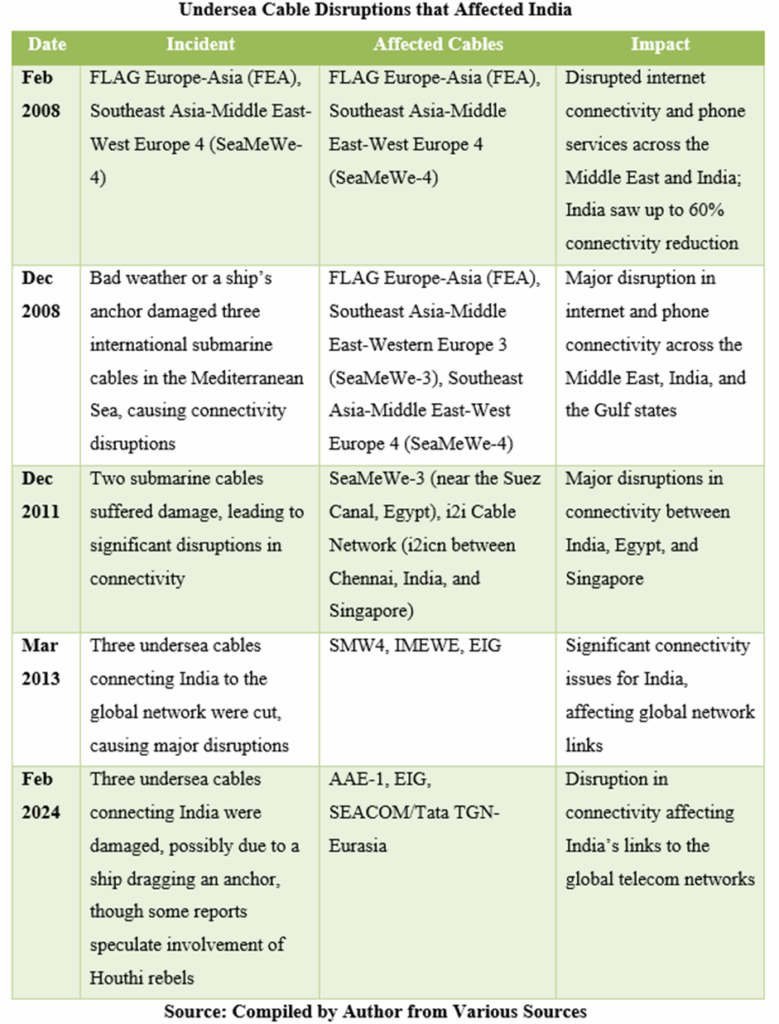

Several undersea cable disruptions have significantly impacted India’s international connectivity. Early incidents—driven by anchor drags and severe weather—hit the FLAG Europe-Asia and SeaMeWe-3/4 systems, at one point slashing India’s internet and phone traffic by up to 60 per cent. Subsequent breaks in December 2011 and March 2013 severed key links on SeaMeWe-3, i2i, SMW4, IMEWE and EIG, causing widespread outages between India and global hubs. The most recent February 2024 event damaged AAE-1, EIG and SEACOM/Tata TGN-Eurasia—likely due to an anchor drag, though some reports speculate involvement of Houthi rebels.

Protection Measures Required to Secure India’s Undersea Cables

Safeguarding undersea cables is vital to maintaining global data flows and internet reliability, necessitating robust legal and practical measures. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ratified by India in 1995, serves as the primary legal framework for protecting these cables, with Article 113 requiring states to criminalize wilful or negligent damage to submarine cables on the high seas. Despite its foundational role, UNCLOS has significant limitations. Its lack of a clear definition for “undersea cable” creates ambiguity, while the absence of a centralized enforcement mechanism relies on national implementation. Drafted in the 1980s, UNCLOS fails to address modern threats such as cyber-attacks or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) capable of damaging or tapping cables, and its protections do not apply during armed conflicts, leaving cables vulnerable in geopolitically tense regions like the Indian Ocean.

Similarly, India’s legal framework for protecting undersea communication cables lacks specificity and comprehensive coverage. The Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 vaguely addresses communication cables, predating modern undersea systems and offering limited relevance. The Maritime Zones of India Act 1976 aligns with UNCLOS, requiring government consent for foreign cable-laying in India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) but lacking explicit protective clauses for cables. Under the Information Technology Act, 2000, Section 70(1) defines a “protected system” as any computer resource whose incapacitation would significantly impact national security, economy, public health, or safety, with the government authorized to designate such systems. While undersea cables could qualify as protected systems due to their critical role in global telecommunications, no explicit designation has been confirmed, and judicial interpretations have primarily focused on digital breaches rather than physical infrastructure. Sections 70A and 70B establish the National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre (NCIIPC) and the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In), respectively, as nodal agencies for protecting critical information infrastructure and responding to cybersecurity incidents. NCIIPC’s mandate to safeguard infrastructure vital to national security could encompass undersea cables, aligning with the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India’s (TRAI) recommendation to include cables under NCIIPC’s oversight. TRAI also urges adding a section to the Telecommunications Act, 2023 to formally recognize cables’ importance and grant “essential services” status to their operation and maintenance. These measures aim to enhance protection, prioritization, and stability for national security and India’s communication network.

Drawing from international models, India could establish Cable Protection Zones within its EEZ, akin to Australia and New Zealand’s frameworks. These zones restrict activities like anchoring and fishing that could inadvertently damage the cables. India could adopt a similar approach by designating zones based on cable density or vulnerability, enforcing them with maritime patrols and legal penalties. Since no international legal framework exists, governments lack the authority to penalize criminals operating beyond their EEZ, even when applying national laws. The global repair industry further complicates protection, with only 70 maintenance and repair ships available, controlled largely by nations like France, Japan, the US, and the UK. This shortage slows down repairs, increasing risks in emergencies. India should collaborate with global partners to strengthen undersea cable security in this situation. The QUAD Partnership on Cable Connectivity and Resilience is working to enhance technical capacity and cable system durability. By investing in infrastructure, maintenance expertise, and rapid response capabilities, India can address growing challenges in cable repairs.

Conclusion

India’s undersea cables are lifelines, driving its digital economy and safeguarding national security, yet they are increasingly at risk from natural disasters, human errors, and deliberate sabotage. The Indian Ocean’s strategic importance heightens these vulnerabilities, threatening disruptions that could cripple India’s connectivity and economic stability. Current legal frameworks, including UNCLOS and India’s existing laws, fail to address modern threats such as cyberattacks or advanced cable-cutting technologies. A ‘universal jurisdiction’ that applies to all countries will likely be the best method to address such concerns, ensuring consistent global enforcement. It could take a while to reach a consensus to accomplish this universality. However, India must take urgent steps to ensure the safety of such vital underwater assets by designating cables as protected systems, establishing Cable Protection Zones, and deepening partnerships with regional countries and groupings like the QUAD. These measures not only safeguard India’s communication networks but also position it as a leader in securing global digital infrastructure.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal.