Anmol Shekhawat is a second-year master’s student at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

China joined the Antarctic Treaty system as consultative party in 1985, with its first Great wall Research Station. This decision was not just based on scientific exploration but rather on a far-sighted strategic perspective about securing a presence in the region. China’s expansion into Antarctica mirrors its Arctic ambitions, securing resources and strengthening global influence. Since 1984, the Chinese National Antarctic Research Expedition (CHINARE) has enhanced technological capabilities and substantial funding in Antarctica pose challenges to historical claimants like Argentina and Chile, who strive to maintain their territorial assertions. Its ability to project presence and conduct complex operations in such a remote and challenging environment demonstrates its comprehensive national strength.

Over the past few decades, there has been a significant transition from a peripheral participant to a major actor in Antarctic affairs. Before the 2000s, China had a limited scientific presence with two stations, later it increased its engagement. The number of papers on Antarctic studies authored by Chinese scientists and indexed in the Science Citation Index (SCI) has increased from 19 in 1999 to 157 in 2016. As noted in the 40th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) meeting, China increased funding for Antarctic research, in the years 2001 to 2016 China spent over 310 million yuan ( around 45 million USD) on various projects- almost 18 times higher than what was spent on these projects from 1985 to 2000.

In the 40th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) held in Beijing in 2017, China’s premier reaffirmed its contributions to global climate studies and introduced the “Green Expedition” concept to encourage eco-friendly Antarctic activities and efforts for enhancing infrastructure to protect the Antarctic white paper released in 2017-18, further solidified its role as a major actor. With China among the top three nationalities of Antarctic visitors while not having any tour operators from China in the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO), emphasized in the 40th ATCM the need for data-driven tourism policies, promoting sustainable travel practices.

China’s expanding presence in Antarctica reflects a strategic balance between scientific collaboration and geopolitical interests. While actively contributing to research and environmental initiatives, its resistance to conservation measures and increasing infrastructural investments suggest broader strategic objectives, prompting concerns about its long-term intentions in the region.

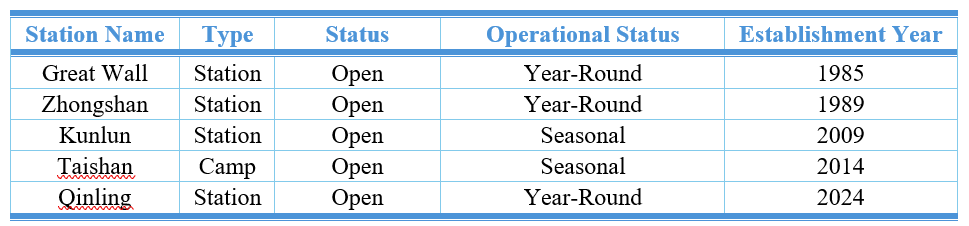

Table 1. List of Functioning Research stations of China in Antarctica

Source: Data cited from Antarctic Treaty Secretariat

China’s Antarctic footprint has grown rapidly through the creation of several research stations, logistical hubs, and icebreaking vessels. In December 2024, China inaugurated its first atmospheric background station, to contribute valuable data to global climate change research. As we see in Figure 1, China currently operates 5 research stations, the newest of which opened in 2024 strategically positioned in East Antarctica, the remotest part of the continent. The East Antarctic Marine Protected Area (EAMPA) was proposed by Australia and the European Union in 2012. Antarctic Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) an advocacy group dedicated to Antarctic conservation, with scientific findings asserts that it is crucial to protect the East Antarctic region, but since the proposal it has been opposed by China and Russia.

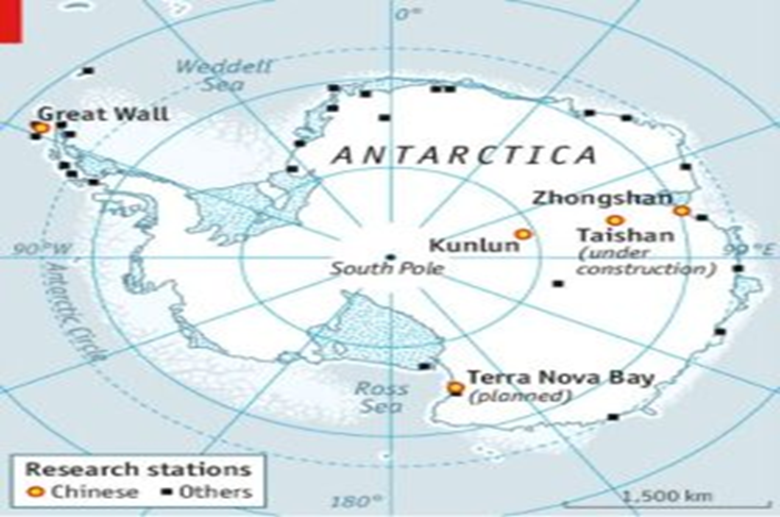

Figure 1. Map representing China’s Research Stations Location

Source: Worldwide Antarctic Program

In Figure 1, the map presents how China has strategically located its stations. The first one in the Antarctic peninsula, as it was an easily accessible area, is currently the most visited tourist site and also the most vulnerable to climate change. By rejecting the Antarctic Peninsula MPA in 2018, China is securing access to marine resources, strengthening its geopolitical influence, and preserving future economic opportunities in fisheries, tourism, and potential resource extraction. The Antarctic Peninsula has historically been the subject of overlapping claims by Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom. The other three stations, namely Zhongshan, Taishan, and Kunlun, are located in the Australian Antarctic Territory, a region historically claimed by Australia. Additionally, Australia has maintained its presence in this territory even after the Antarctic Treaty banned all claims, with its stations: Casey Station (established in 1969), Davis Station (1957), and Mawson Station (1954).

China’s presence in the Antarctic Peninsula enhances climate studies while positioning it in a contested region. Stations in the Australian Antarctic Territory signal interest in resource-rich areas, potentially challenging territorial norms in future. The newest East Antarctic station expands China’s reach into a remote yet scientifically valuable region, reinforcing both research and strategic ambitions. Chinese researchers have also conducted extensive studies on Antarctic Krill populations, which play a crucial role in the Southern Ocean ecosystem. The studies on marine ecosystems by China have an underlying interest, as Chinese officials label krill harvesting as “sustainable”, but the krill and toothfish are an important part of the Southern Ocean and Antarctic marine ecosystem.

In the 2024 Consultative Meeting, China reaffirmed its step-by-step approach to New MPA designation, stressing the need to refine Conservation Measure (CM) 91-04 before revising proposals. It also maintained that climate change, while relevant, is not the primary objective of the CAMLR Convention and requires further discussion and advocated easing the restrictions on krill fishing. Specifically, they opposed proposals for four new marine parks aimed at conserving Antarctic marine ecosystems. The Ross Sea MPA was first proposed in 2012 and established in 2016 after years of negotiation and compromises were made to accommodate the interests of both China and Russia. The instance of the Ross Sea showcases how China has emerged as a major actor in influencing Antarctic governance. China’s opposition to the creation of MPAs, raising questions about its environmental commitments.

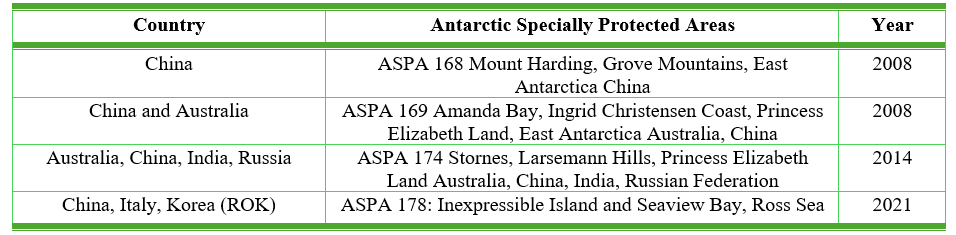

Table 2. Number of Designated Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPA) proposed and managed by China

Source: Antarctic Treaty Secretariat

China’s Antarctic strategy has been characterized by both collaboration and assertiveness. Figure 3, mentioning the 4 ASPA regions managed and proposed by China, showcases its commitment to conservation measures with collaboration. China has also engaged in joint projects with countries like the United States, Russia and Germany, particularly in the areas of ice core drilling, marine biodiversity research, and climate change studies. The Kunlun Station near Dome A is a key site for deep ice-core drilling, providing valuable insights into historical climate patterns, in the 40th ATCM China had also proposed to draft a code of conduct for the same site to the Committee for Environmental Protection, balancing its economic interest with conservation efforts. China also collaborated with Australia, India, and Russia in proposing and managing Antarctic Specially Managed Area No. 6 in Larsemann Hills. While the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) forbids any military activities or mineral extraction in Antarctica, China’s long-term strategic goals are illustrated through its “Polar Silk Road” Belt and Road Initiative in the Northern polar region, signalling its long-term economic interests in the southern polar region.

At the 46th ATCM held in India in 2024, China actively voiced for science-based decision-making and integration of climate change considerations in Antarctic governance, it also emphasized on need for a clear definition and criteria for vulnerability in the Antarctic environment. China opposed restrictions on human activities in marine and terrestrial areas presented by working paper 38. It challenged the expansion of ASPA 139, arguing that the inclusion of marine areas lacked scientific justifications, it also questioned the designation of emperor penguins as a specially protected species, suggesting existing measures were sufficient.

On the other hand, it was seen promoting and practising renewable energy to reduce dependence on fossil fuel in Antarctica by proposing a Working Paper (WP) 16. China showcased its net zero emissions achievement at Taishan Summer Camp (2018-19) and Qinling station (Ross Sea region), advocating for a manual outlining renewable energy strategies, also recommended collaboration with the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) to develop a manual on best practices for renewable energy use in Antarctica. Its approach in 2024 was seen to lean more towards strategic interest with selective environment advocacy.

Although the Madrid Protocol currently prohibits mineral extraction in Antarctica, China’s extensive geological surveys and enduring presence may lead it to strategic advantage if the moratorium is reconsidered after 2048. China’s strategy towards Antarctica is a compromise between state interests and international image. From one angle, China’s investment in scientific research and building new installations could imply that Beijing is attempting to contribute to the understanding of Antarctica and its climatic regulation functions. From another approach, resistance to preservation initiatives suggests a much stronger prioritization of economic interest oriented, than of environment conservation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal.