Hoimontick Gogoi is a second-year master’s student at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

Negotiation in international relations refers to the use of mechanisms such as strategic dialogue and compromise to establish cordial relations between two political entities. In the context to China-U.S. negotiations, it has provided a framework to deal with economic interests alongside security concerns and geopolitical ambitions. As political scientist Robert Putnam (1988) suggests through his two-level game theory, the important factors that international negotiations are based on which includes both domestic and international factors. The leaders are required to deal with all the socio-political dynamics of their country while engaging with foreign counterparts. One of the major features of this theory is the “win set” concept which details the range of possible agreements. The objective is to satisfy both constituents at the domestic level and international level of the negotiation sides. The “win set” represents the linkage of the domestic stakeholders desire and what can realistically be negotiated with other nations. United States Mexico Canada Agreement (USMCA) is one of the most notable examples in relation to the two-level game theory. During the USMCA negotiations, US decision makers for the ‘win set’ in this case included stronger labour, tougher auto standards to win support from labour unions and congressional Democrats. The integration of these domestic factors shows their influence in creating a win-set in negotiations. This theory is relevant in the case of China and the U.S. due to several factors such as economic policies, political ideologies, and international conflicts like the Russian-Ukraine conflict have played a crucial role in shaping the way negotiations take place. With so much on the line, negotiations between China and the U.S. extend beyond mere diplomatic talks to more high-stakes strategic discussions where both nations have tried to maximise their interests and gains.

In 2017, when former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, was asked about China’s bottom line for a healthy and sustainable China-U.S. relationship had stated that “President Trump and senior officials from the new US administration have explicitly reaffirmed continued US adherence to the one-China policy, which forms the political foundation of China-US relations. This foundation has remained firm and unshaken despite changing circumstances, and it would always remain so in the future. With the right political foundation in place, China-US cooperation enjoys bright prospects.” So, under the second Trump administration, we need to look at how negotiations might go, not as a matter of speculation but by comprehending on the significant questions of why countries negotiate, what pushes them to do so, and how both nations push for their interests within a structured diplomatic process.

Why do China and the U.S. negotiate? The Core motivations

States primarily engage in negotiations because of various economic, security, and strategic goals along with their efforts to manage their international image. Kenneth Waltz argues that “even the prospect of large absolute gains […] does not elicit their cooperation so long as each fears how the other will use its increased capabilities”. The dynamics that are seen in US-China negotiations reflect their joint challenges regarding trade imbalances along with technological rivalry while also considering military strategies and aspirations for global dominance. Both countries require negotiations to go on due to their economic interdependence because a complete breakdown in relations would lead to substantial costs.

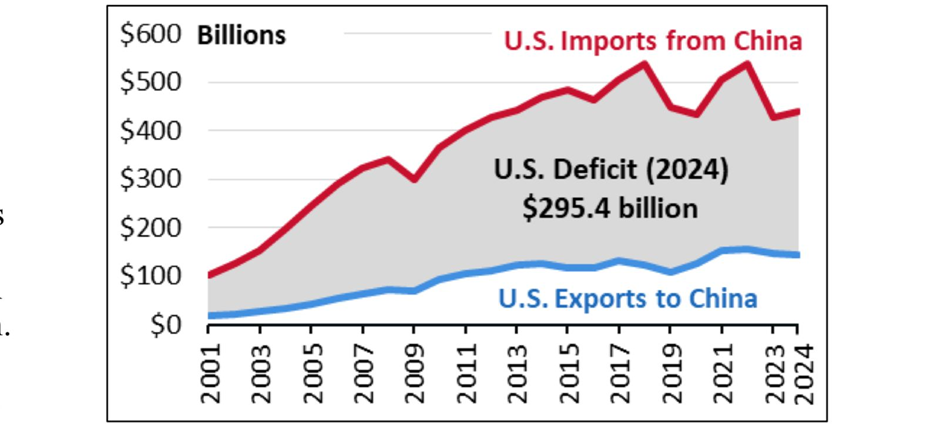

Figure 1. U.S. Imports and Exports from China

Source– Sutter, 2025

Even with the recent buildup of tensions between them, China and the United States remain economically interdependent. In 2024, the percentage of U.S. exports sent to China dropped by 2.9 percent, falling from US$147.78 billion in 2023 to US$143.55 billion. On the other hand, the U.S. imports from China increased by 2.7 percent during the same time, rising from US$426.89 billion in 2023 to US$438.95 billion in 2024. This resulted in the U.S. trade deficit with China widening by roughly US$16 billion from 2023 to 2024. President Trump’s economic strategy of employing tariffs and trade restrictions was meant to push China into making some major changes to its economic outlook, particularly by setting an ambitious growth target of around 5 percent for 2025. China also shifted its focus towards increasing its domestic consumption and increasing fiscal spending to counteract the impacts of tariffs and trade tensions. Analysts opined that Beijing has shown restraint in its response to leave room for negotiations. However, these tariffs imposed during the first trade war did not decrease U.S. reliance on Chinese goods. Instead, they caused prices for consumers in the U.S. to go up and made companies rethink the sourcing of materials. Chinese officials have consistently emphasized negotiation as the key to resolving trade disputes, with Vice Premier Liu He during the second round of economic and trade consultation with the U.S. stating that, “ Negotiation will always bring about lower costs and greater benefits than confrontation ”.The Trump administration was pushing hard for concessions, but China took a more cautious and practical approach.

An intriguing event during this period was Henry Kissinger’s two visits to China in 2018. Beijing was hoping that he would pave the way for successful talks between President Xi and President Trump on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Argentina. During that period, Chinese scholar Shen Dingli emphasized on the fact that “The Chinese leaders believe they must find someone reliable to talk with and convey a message to Trump”. Apart from trade, these negotiations were also a way to keep a lid on security issues, especially in the Indo-Pacific area. The U.S. strategy for the Indo-Pacific had ramped up tensions due to the U.S. engaging with countries like Japan, Australia, and India on military matters. Meanwhile, China has been building its navy and expanding infrastructure in contested areas of the South China Sea which led them to declare the ten-dash line. Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs made its position clear, by stating: “China stands ready to continue to resolve the relevant disputes peacefully through negotiation and consultation with the states directly concerned on the basis of respecting historical facts and in accordance with international law.”

A key shift in Trump’s first term saw the U.S. retreat from multilateral institutions, while China embraced a globalist strategy through initiatives like the BRI. The U.S. exited deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), leaving a vacuum of leadership that China sought to fill. The BRI pledged over US$1 trillion in infrastructure ventures spanning Asia, Africa, and Europe, embodying China’s plan to broaden its economic and political reach. The U.S. policymakers countered the BRI denouncing it as an “accrual and manipulation of debt”; and claiming that China’s method of financing sets up economic dependency for the recipient countries. President Xi Jinping has countered this assertion stating, “We should foster a new type of international relations featuring win-win cooperation; and we should forge partnerships of dialogue with no confrontation and of friendship rather than alliance ”. The negotiations over these global initiatives mirror the larger struggles for cooperation between the two superpowers.

These negotiations have been further complicated due to evolving technological and military competition. The Trump administration’s ban on Huawei and TikTok epitomizes this contest for technological supremacy, especially in areas like 5G, semiconductors and artificial intelligence. President Xi has suggested that “Scientific and technological innovation has become the main battlefield of the international strategic game, and the competition around the commanding heights of science and technology is unprecedentedly fierce”

The rationale behind China-U.S. negotiations stances

Each country comes to the negotiating table with a position and a mandate to strive for gains. The U.S. has accused China of being an unfair trader — specifically concerning elements such as theft of intellectual property, subsidization of national industries and manipulation of its currency. Such concerns were at the core of Trump’s trade war, with his administration demanding structural changes to China’s economic system. Trump’s economic adviser in his first term Peter Navarro (2020) characterised China’s actions as “economic aggression,” solidifying a hardline stance that guided U.S. trade policies towards China. In addition to that, American companies wanted more market opportunities and protection of intellectual property rights while reducing their dependence on Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

As a fundamental principle of negotiation, China adheres to the core principle of sovereignty and non-interference to establish reciprocal agreements. The Chinese government continues to declare that it will reject all agreements that harm its national interests while demanding neither unbalanced compromises nor surrender. China has also refused to accept any agreement that would harm its national interests or require it to accept unilateral terms. In trade negotiations with the United States, China adheres to three principles; First, it seeks to remove American regulations on Chinese technology companies that are seen as impediments to healthy innovation and rivalry. Second, China hopes to ensure that its linkage to U.S. financial markets is secured, which is critical for foreign capital investment and promoting the international use of renminbi. Finally, China strives to protect its trade balance from American protectionist policies and supports the need for a liberalized free trade system which lessens the adverse effects of one-sided trade policies that can disturb international supply chains and economic relations. Hence, with the geopolitical tensions in both countries at the forefront, negotiations become a tool to reduce competition rather than removing fundamental conflicts. Henry Kissinger rightly stated in this regard that, “If our two countries cooperate, we can contribute to solving the problems of the world. But if we quarrel then it will make it difficult anywhere else to have progress.”

Conclusion: Will China and U.S. negotiate under Trump 2.0

The prospects for China-U. S. negotiations under the Trump 2.0 administration will depend on the convergence of domestic economic concerns, security and geopolitical priorities. While negotiations have strategic benefits for both sides, diplomacy is still vital to avoiding a full-blown economic or military confrontation. There are three potential paths to be expected. First, a setting of managed competition could come about in which structured processes of negotiation limit escalation, incrementally addressing trade and security issues. Second, if tensions spur more tariffs, technological restrictions, and military confrontations, a path towards economic and strategic “decoupling” is very much possible. Third, a model of selective engagement might emerge, with cooperation persisting in narrow areas like climate change and global health. The question, however, is to what extent the Trump administration would work and cooperate on global problems concerning all nations. Considering the administration’s generally pronounced skepticism towards climate-related activities, especially during Trump’s first term as the President, it seemed that substantial cooperation in this regard was highly problematic Nonetheless, the rise of powerful private actors such as Musk, especially with Tesla’s strong interests in China, could be conducive to enabling American-Chinese dialogue on essential concerns. This signals that while cooperation through government channels may be difficult, there can be unilateral action from the private side to deal with important shared problems. As Henry Kissinger (2011) cautioned, “ How the US and China conduct their relationship in coming years will depend on the patience and diplomacy of its leaders”. In the end, negotiations will be a continuing feature of China-U. S. relations and their impact will depend on the political readiness of both sides to balance competition as well as cooperation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal.