Thumar Yatharth Vrajeshbhai is a second-year master’s student at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

The relationship between China and Russia has grown stronger in recent years. On 16 May 2024, both countries commemorated the 75th anniversary of diplomatic relations as the “China-Russia Years of Culture.” At the opening ceremony in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping posited “consolidating and developing enduring good-neighbourly friendship,” Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that the ties are “now at their best in history.” This celebration coincides with the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, which has cast a spotlight on China’s tight connections with Russia. Over the past two decades, especially since the War in Ukraine, Beijing and Moscow’s cooperation in trade and defence has deepened. However, some tensions persist. Despite not being official treaty allies, their expanding partnership—particularly in the context of the Russia-Ukraine War—raises an important question: How did the ‘War’ act as a catalyst to strengthen their relations?

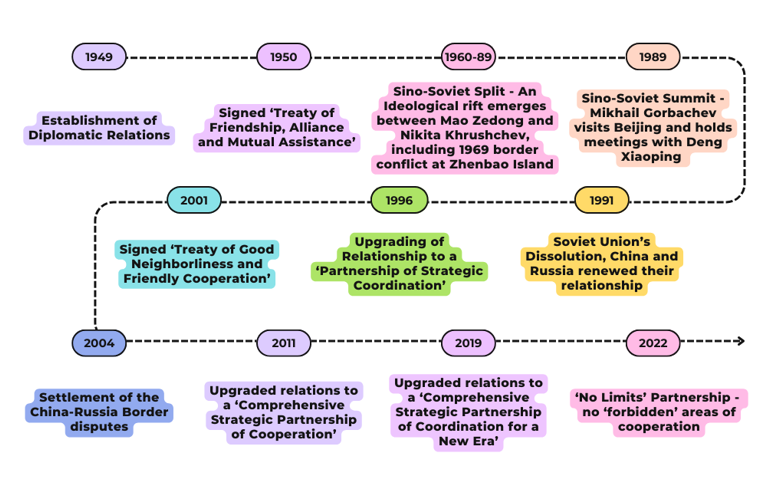

Figure 1. Evolution of China-Russia Ties

Source – Compiled by the Author

The China-Russia relationship is built on mutual respect and the recognition of each other’s core interests, shaped by a history of both cooperation and competition (see Figure 1). In February 2022, just days before Russia launched its “special military operation” in Ukraine, Xi and Putin met and issued a joint statement reaffirming their ties being “superior to political and military alliances of the Cold War era,” and that their friendship has “no limits” with “no forbidden areas of cooperation,” and that “their strategic cooperation is not directed against third countries or influenced by external changes.” This echoed an earlier remark in 2021, by then-Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng, who stated that “there is no limit to the friendship, no forbidden zone to the cooperation and no ceiling to the mutual trust.”

The Russia-Ukraine war has significantly impacted the Beijing-Moscow dynamics. It has forced Russia to turn away from Europe and seek closer ties with China as Western sanctions have isolated Moscow economically and diplomatically. Since the onset of the war in 2022, on one end, China has consistently voiced rhetorical support for Russia and opposed all sanctions against Russia, and its 12-point peace plan (released in 2023) calls for de-escalation, ceasefire, and preventing wider conflict, potentially nuclear war. All along, China has also been cautious in balancing its ties with Russia while avoiding confrontation with the West, as it seeks to protect its economic interests, maintain stable trade relations, and prevent diplomatic isolation. While the US had opposed China’s stance, viewing it as tacit support for Russia, the European Union (EU) and Ukraine have also rejected it, arguing that it lacks a clear call for Russia to withdraw from occupied Ukrainian territories and fails to hold Russia accountable for invasion.

In the backdrop of the War, one of the prominent aspects that has come to the forefront is the Xi-Putin dynamic, in shaping China-Russia ties over the past decade. Since taking power in 2012, Xi has met Putin around 46 times (one-on-one meetings and virtual meetings, excluding telephone calls), more than twice as often as Xi has met any other world leader. And since the War in Ukraine, both leaders visited each other’s countries twice and met in person six times (see Figure 2). After securing the third term, Xi’s first foreign trip was to Russia in March 2023, just as Putin’s first trip after his fifth term in May 2024 was to China. This mutual choice over their first visits highlights the priority factor placed by the leadership vis-à-vis the other.

Figure 2. Xi and Putin’s diplomacy since the Russia-Ukraine War

Source – Compiled by the author with reference to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China.

Under, Putin, Russia has aligned with many of Xi Jinping’s key international priorities, such as endorsing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and supporting China’s Global Development Initiative. While tangible progress on linking the BRI with Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union has been limited, its support reflects a strategic alignment with Beijing’s global vision. Russia has also joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, further demonstrating its readiness to back China’s global ambitions.

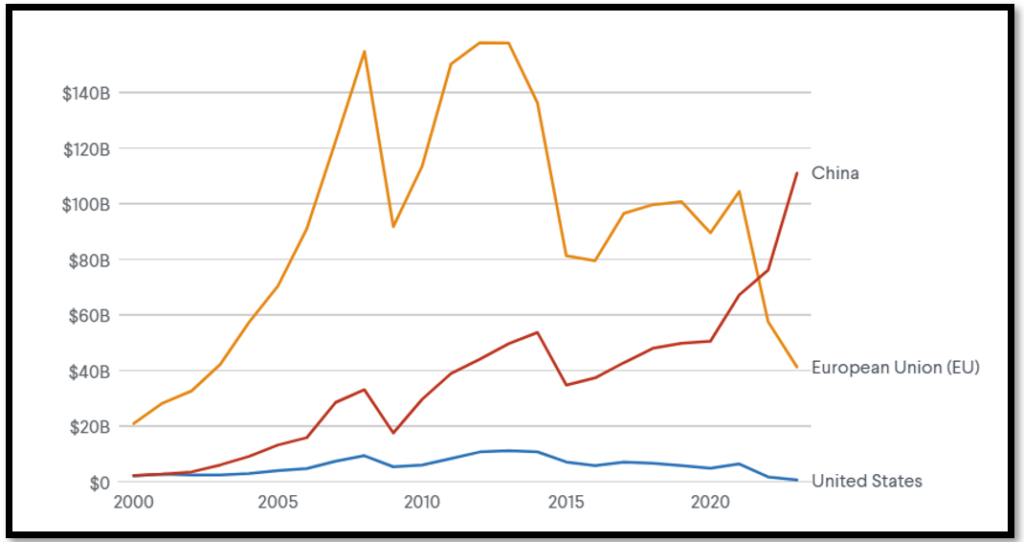

The Russia-Ukraine war has significantly intensified economic cooperation between China and Russia, acting as a catalyst in bringing the economies closer, while reducing dependence on Western markets amid escalating sanctions. Bilateral trade between them has increased steadily over time, but since the War in Ukraine, it has skyrocketed- reaching US$240 billion in 2023, up from US$147 billion in 2021, with the surge surpassing their 2024 target of US$200 billion, ahead of schedule. China has become Russia’s largest trading partner, accounting for approximately 26 percent of Russia’s total trade, while Russia represents a mere 3 per cent of China’s trade portfolio, highlighting a significant asymmetry in their economic relationship. As the EU slashed exports to Russia by roughly 60 per cent since the onset of the war, China filled the void by boosting its exports to Russia by 65 per cent since 2021, reaching over US$110 billion in 2023 (Figure 3). These exports include vehicles, machinery, home appliances, etc.

Figure 3. Exports to Russia

Source – Council on Foreign Relations

On the energy front, Russia has become China’s oil supplier, overtaking Saudi Arabia, as China capitalise on discounted Russian fuel. This shift has further deepened their energy ties, even as China’s increasing focus on renewable energy suggests potential changes in future. However, China views Russia as one of many economic partners, whereas Russia relies significantly on China for trade and investment, particularly following the war in Ukraine and Western sanctions. If the war continues, Russia will need economic backing, and it must keep China close, especially given the possibility of global isolation.

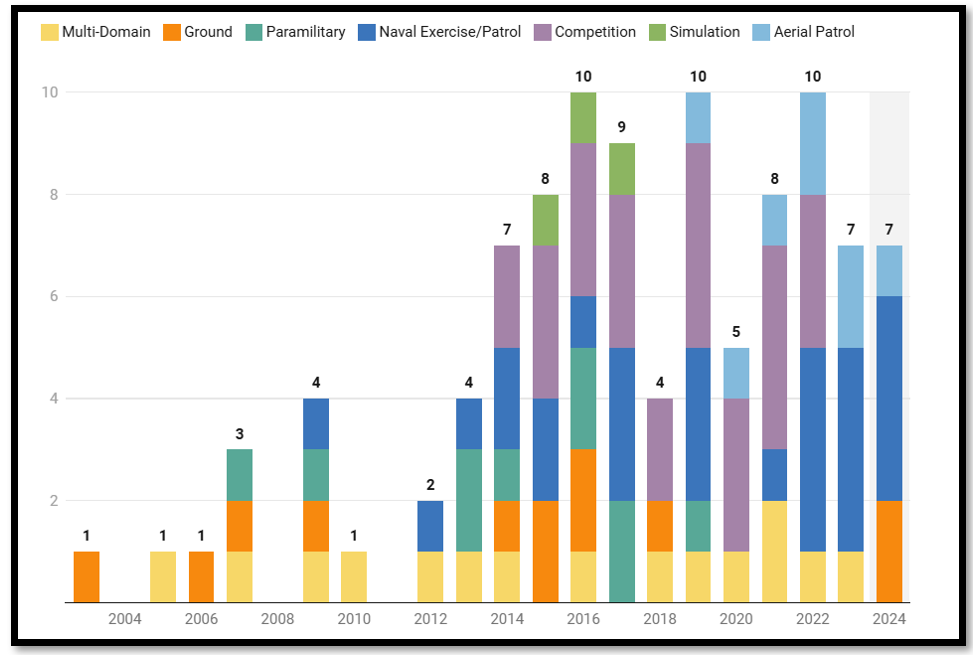

Military cooperation between China and Russia has been a crucial aspect of their relationship, characterised by substantial arms sales and technological exchanges. Since the war began, China and Russia have deepened their defence cooperation. Joint military exercises have become a key component of military ties, starting with the multilateral exercise, Coalition 2003 counterterrorism drills under the SCO. The first bilateral military exercise, Peace Mission 2005, paved the way for a growing number of joint drills over the years across different domains. Through July 2024, the two nations conducted at least 102 joint military exercises, more than half of which occurred since 2017. Their joint exercises have expanded geographically, moving from Western China and Central Asia to distant regions like the South African coast, Mediterranean Sea, Bering Sea, and Baltic Sea. They have also conducted joint aerial patrols across the Pacific Ocean, reflecting a broader operational reach.

Figure 4. China-Russia joint military exercises (as of August 7, 2024)

Source – China Power

Initially, Russia provided crucial arms and technology to bolster China’s defence capabilities. Between 1990 and 2005, China sourced over 83 percent of its arms imports from Russia, totalling US$10-11 billion. However, China’s reverse engineering of Russian technology including aircraft engines, Sukhoi planes, deck jets, air defence systems, portable air defence missiles, and analogs of the Pantsir medium-range surface-to-air systems, has strained the partnership. Since 2005, Russian arms sales to China have declined, while China’s defence industry has advanced significantly. The Russia-Ukraine war caused Russia’s global arms export share to fall from 8.8 per cent in 2021 to just 4 per cent by 2023, while China’s share increased to 8.4 per cent during the same period, overtaking Russia. China has refrained from providing direct military aid to Russia but has indirectly supported it through dual-use goods such as drones, machine tools, and semiconductors. This flow of critical components has deepened Russia’s reliance on China, as its defence industry struggles under Western sanctions.

China and Russia have strengthened their coordination within multilateral organisations such as the United Nations Security Council (by aligning voting patterns), BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) to promote a multipolar world order that challenges Western dominance. Through these platforms, they seek to expand their influence, advocate alternative governance models, and counterbalance the US hegemony. In BRICS, both countries have played a key role in pushing for expansion, reinforcing the group’s global standing. The recent inclusion of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates reflects their commitment to broadening the coalition’s reach. Similarly, within the SCO, China and Russia prioritise regional security and economic cooperation, engaging in joint military exercises and counterterrorism initiatives. The organisation serves as a critical platform for coordinating policies and presenting a united front on regional issues, further strengthening their strategic partnership. While their collaboration in these organisations bolsters their geopolitical influence, underlying asymmetries in their relationship could create friction, particularly in areas where their strategic interests diverge.

The Russia-Ukraine war has undoubtedly strengthened China-Russia relations, but the partnership has its limits. While China initially embraced the “no limits” narrative, it has since set boundaries avoiding direct military aid, rejecting key proposals like the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, and prioritising its own strategic interests. Despite these limits, the war has deepened their economic, military, and diplomatic ties, challenging the Western-led global order. However, a growing asymmetry is emerging, with Russia increasingly appearing as the junior partner, creating potential friction points. As Russia becomes more dependent on China for economic and technological support, China secures Russian energy and strengthens its geopolitical position. Meanwhile, Russia remains wary of China’s expanding influence in its traditional sphere of influence, particularly in Central Asia, where Beijing’s economic dominance is reshaping regional dynamics. Thus, China in its ways dictates the limits of this relationship, ensuring it serves its long-term strategic interests and goals.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal.